Chapter 5: Kesa Dimensions

Compared to Western clothing, the kesa is flexible in its measurements. That said, for the robe to look good and be in proper order, it’s important to use an individual’s measurements.

Size is determined giving consideration to three factors: practicality, proper positioning, and the principle of not arousing desire. To fulfill these three requirements is to naturally arrive at the proper size.

Let’s consider the dimensions of the robe, both overall and section-by-section.

1. Overall dimensions (vertical and horizontal)

There are two methods: direct and indirect.

Size is determined giving consideration to three factors: practicality, proper positioning, and the principle of not arousing desire. To fulfill these three requirements is to naturally arrive at the proper size.

Let’s consider the dimensions of the robe, both overall and section-by-section.

1. Overall dimensions (vertical and horizontal)

There are two methods: direct and indirect.

|

Direct Method (度身法, doshinhō)

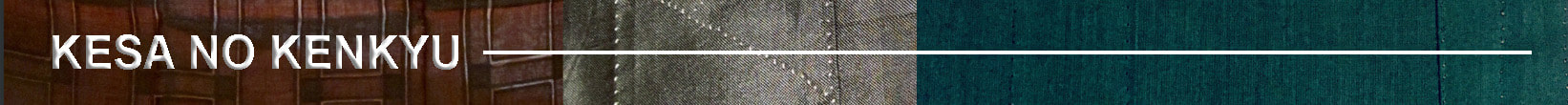

From Hōbukukakushō: "In the method of doshin, one hangs the robe from the shoulder toward the ground; four fingers’ width above the ankle is the proper length. Inner garments and jikitotsu (直綴) should be adjusted to reach the instep. This is the vertical amount. Grabbing the corner of the robe, wear it over your shoulders to the armpit; this is the horizontal amount." In these ways, one can measure the overall vertical and horizontal lengths directly against the full body. 1 It’s important to keep in mind that these are the measurements of the completed robe, not the cut measurements. As an illustration, using the direct method, a robe based on my own size would measure 115cm high and 195cm wide. This is my basic measurement. |

|

Indirect Method (局量法, kokuryōhō)

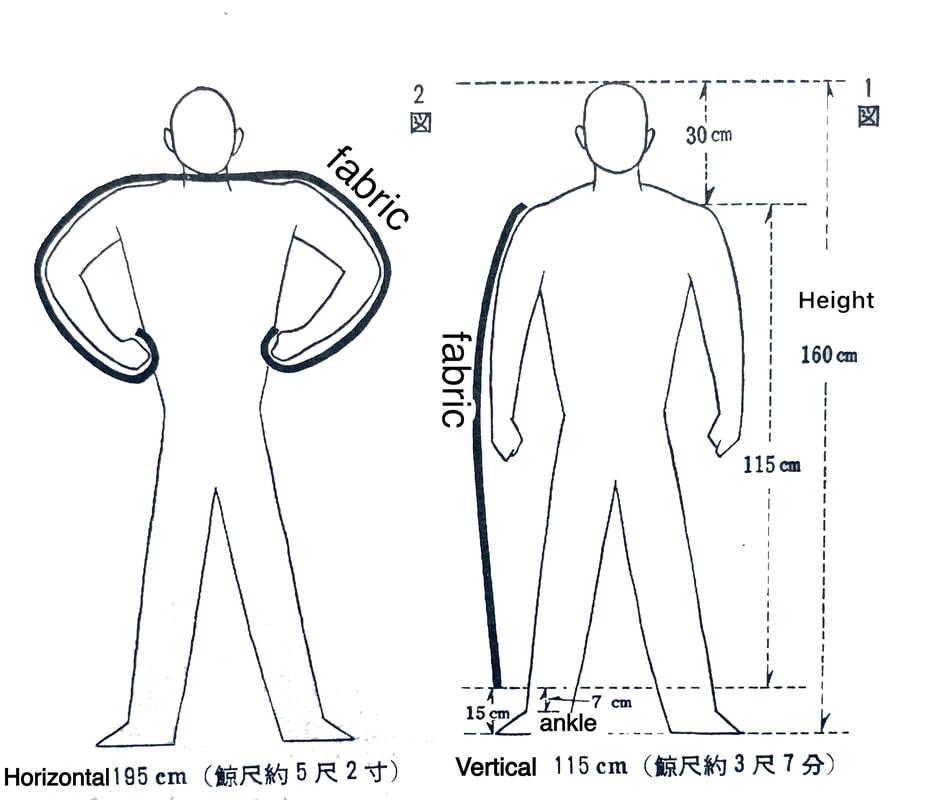

In this method, measurements are calculated according to just a part of the body. When calculating the overall measurements, we rely on measurements such as chū (based on the arm), and chōshu or takushu (based on the hand). When calculating the sections, takushu, a finger’s width, or sizes relative to wheat or a bean are used to establish standards. Chū (肘) There is nobechū (舒肘), or outstretched chū (from the tip of the elbow to the tip of the middle finger), and there is kenchū (拳肘, closed chū, elbow to the knuckle). My measurements can be seen in the figures at right. |

|

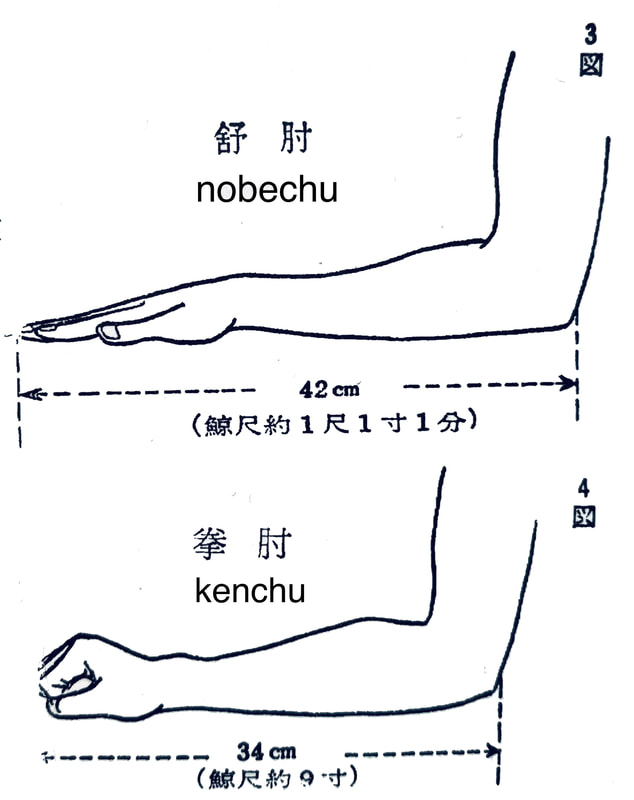

Takushu/Chōshu

With fingers fully outstretched, the distance from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the middle finger is called one “cross hand” (磔手, takushu) or one “stretched hand” (張手, chōshu). Finger The width of the finger’s first joint is called “one finger.” The width of twenty-four fingers is equal to two stretched hands, which is equivalent to one chū. But it may not be exact. The measurement of the full kesa, then, can be established using any one of the three measurements. |

According to Malasarvastivada Vinaya Samgraha:

Samghati (sōgyachi; 9-jō to 25-jō Kesa)

A large-size kesa is 3 chū (vertical) by 5 chū (horizontal); small is 2.5 chū by 4.5 chū; medium is in between.

Uttarasangha (utarasōgya; 7-jō kesa)

Large, medium, and small measurements are the same as for the samghati.

Antarvasa (andae; 5-jō kesa)

Large is 2 chū by 5 chū; small is 2 chū by 4 chū.

Based on the above, there are five possible measurements. However, other vinaya state that the maximum size is 3.5 chū by 6 chū, so the measurements are not at all standardized. Further, in the commentary on the Sarvastivadin Vinaya, it is said that “the true robe is three by five chū,” so we can also consider that as a standard measurement. (That said, it is not clear in this case if one chū refers to an outstretched chū or one measured to the knuckle.)

Based on the standards outlined above, my own measurements are as follows for a 7- to 25-panel kesa, using outstretched chū:

Large: 3 chū = 126 cm

5 chū = 210 cm

Medium: 2.75 chū = 115.5 cm

4.75 chū = 199.5 cm

Small: 2.5 chū = 105 cm

4.5 chū = 185 cm

If we experiment and compare the outcomes of the direct method and the indirect method, we find that the medium measurement is roughly the same for both.

Taking into account these two methods as well as the actual experience of wearing the robe, I have settled on the following approach to measurement: depending on the person, given that there is a considerable gap between the chū measured to the outstretched finger and the chū measured to the knuckle, either one may be appropriate. Chū can also be established by finding the average between the two, or by subtracting a fixed length from the outstretched chū. Regardless, we can say that the overall dimensions of the kesa keep a ratio of three vertical chū to five horizontal chū.

Whether we take up the direct or indirect method, the fact is that measuring things was not so serious a question for the people of ancient India. Those of us who sew the kesa today follow very detailed measurements, but originally, the kesa began as an object that was measured roughly, based on estimates. So we need not be overly concerned with measurements.

Partial Dimensions

Yō

The origin of the term yō (葉,literally “leaf”) comes from Rokumotsuzu Jutsugi 2 , in which it is written, “Yō is so named because it resembles the overlapping of leaves on a tree.” However, in looking at the rice field pattern of the kesa, we see the yō as the raised footpath between paddies.

The width of vertical and horizontal yō must be the same. How is that width determined?

In Kikiden it is written, “Interior yō should be three fingers; the border should be one sun.” 3

According to Hōbukuzugi Ryakuhon, at maximum the yō should be 4 fingers’ width, and at minimum the size of barley. In the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, the yō of a large kesa is 4 fingers wide; medium, 3 fingers; and small, 2 fingers.

In short, the yō is limited to 4 fingers wide (2 sun, or 7-8 centimeters) at the widest, but there are some differences in approach to determining the minimum width.

Further, depending on the number of panels—and by extension, the width of each panel—the yō must be narrow to remain proportionate. There are also cases in which the cloth itself necessitates a narrower yō. Regardless of the circumstances, however, it is always the case that the yō is narrower than the panel itself.

Typically, in the case of a seven-panel kesa, we follow the standard in Kikiden: a 3-finger wide yō. In reality, the width of a finger varies according to each individual. But with the seven-panel kesa, taking into account overall balance, the width of a standard bolt of cloth, and so on, the standards for determining yō outlined later (in chapter 9) are appropriate.

It should be noted that in the case of the kussho-e—which is limited to the five-panel kesa—because the yō is eked out from the panel cloth, it is necessary to make the yō quite narrow. Also, the vinaya makes clear that dyeing the yō a different color, as well as painting the kesa to give the appearance of yō, are both considered unacceptable.

Border (en)

The thin border of cloth forming the circumference of the kesa is referred to as the en, or sometimes as the heri.

In Hōbukukasangi, we read, “In the true school [which follows the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya], border and yō have the same width; in the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, yō is 3 fingers’ width and border is one sun.” We see that in the new translation of Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, the border is slightly narrower than the yō; in the older vinaya, they’re the same.

The border’s original function was practical (to fortify the outer edge of the kesa, which is easily damaged) so it didn’t have clear rules regarding measurements. However, over time, conventions developed, and measurements became fixed. Ordinarily, we follow the rule of making the border narrower than the yō. But whether we do or not, there is no case in which the yō is narrower than the border.

Samghati (sōgyachi; 9-jō to 25-jō Kesa)

A large-size kesa is 3 chū (vertical) by 5 chū (horizontal); small is 2.5 chū by 4.5 chū; medium is in between.

Uttarasangha (utarasōgya; 7-jō kesa)

Large, medium, and small measurements are the same as for the samghati.

Antarvasa (andae; 5-jō kesa)

Large is 2 chū by 5 chū; small is 2 chū by 4 chū.

Based on the above, there are five possible measurements. However, other vinaya state that the maximum size is 3.5 chū by 6 chū, so the measurements are not at all standardized. Further, in the commentary on the Sarvastivadin Vinaya, it is said that “the true robe is three by five chū,” so we can also consider that as a standard measurement. (That said, it is not clear in this case if one chū refers to an outstretched chū or one measured to the knuckle.)

Based on the standards outlined above, my own measurements are as follows for a 7- to 25-panel kesa, using outstretched chū:

Large: 3 chū = 126 cm

5 chū = 210 cm

Medium: 2.75 chū = 115.5 cm

4.75 chū = 199.5 cm

Small: 2.5 chū = 105 cm

4.5 chū = 185 cm

If we experiment and compare the outcomes of the direct method and the indirect method, we find that the medium measurement is roughly the same for both.

Taking into account these two methods as well as the actual experience of wearing the robe, I have settled on the following approach to measurement: depending on the person, given that there is a considerable gap between the chū measured to the outstretched finger and the chū measured to the knuckle, either one may be appropriate. Chū can also be established by finding the average between the two, or by subtracting a fixed length from the outstretched chū. Regardless, we can say that the overall dimensions of the kesa keep a ratio of three vertical chū to five horizontal chū.

Whether we take up the direct or indirect method, the fact is that measuring things was not so serious a question for the people of ancient India. Those of us who sew the kesa today follow very detailed measurements, but originally, the kesa began as an object that was measured roughly, based on estimates. So we need not be overly concerned with measurements.

Partial Dimensions

Yō

The origin of the term yō (葉,literally “leaf”) comes from Rokumotsuzu Jutsugi 2 , in which it is written, “Yō is so named because it resembles the overlapping of leaves on a tree.” However, in looking at the rice field pattern of the kesa, we see the yō as the raised footpath between paddies.

The width of vertical and horizontal yō must be the same. How is that width determined?

In Kikiden it is written, “Interior yō should be three fingers; the border should be one sun.” 3

According to Hōbukuzugi Ryakuhon, at maximum the yō should be 4 fingers’ width, and at minimum the size of barley. In the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, the yō of a large kesa is 4 fingers wide; medium, 3 fingers; and small, 2 fingers.

In short, the yō is limited to 4 fingers wide (2 sun, or 7-8 centimeters) at the widest, but there are some differences in approach to determining the minimum width.

Further, depending on the number of panels—and by extension, the width of each panel—the yō must be narrow to remain proportionate. There are also cases in which the cloth itself necessitates a narrower yō. Regardless of the circumstances, however, it is always the case that the yō is narrower than the panel itself.

Typically, in the case of a seven-panel kesa, we follow the standard in Kikiden: a 3-finger wide yō. In reality, the width of a finger varies according to each individual. But with the seven-panel kesa, taking into account overall balance, the width of a standard bolt of cloth, and so on, the standards for determining yō outlined later (in chapter 9) are appropriate.

It should be noted that in the case of the kussho-e—which is limited to the five-panel kesa—because the yō is eked out from the panel cloth, it is necessary to make the yō quite narrow. Also, the vinaya makes clear that dyeing the yō a different color, as well as painting the kesa to give the appearance of yō, are both considered unacceptable.

Border (en)

The thin border of cloth forming the circumference of the kesa is referred to as the en, or sometimes as the heri.

In Hōbukukasangi, we read, “In the true school [which follows the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya], border and yō have the same width; in the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, yō is 3 fingers’ width and border is one sun.” We see that in the new translation of Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, the border is slightly narrower than the yō; in the older vinaya, they’re the same.

The border’s original function was practical (to fortify the outer edge of the kesa, which is easily damaged) so it didn’t have clear rules regarding measurements. However, over time, conventions developed, and measurements became fixed. Ordinarily, we follow the rule of making the border narrower than the yō. But whether we do or not, there is no case in which the yō is narrower than the border.

|

Cord

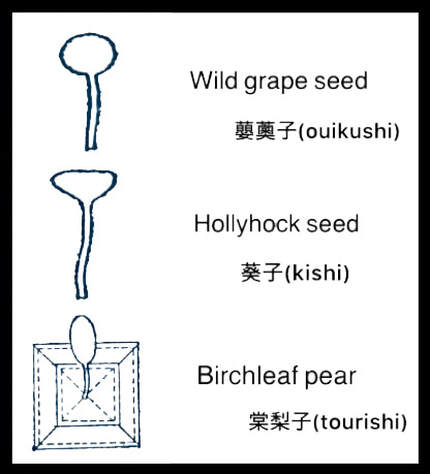

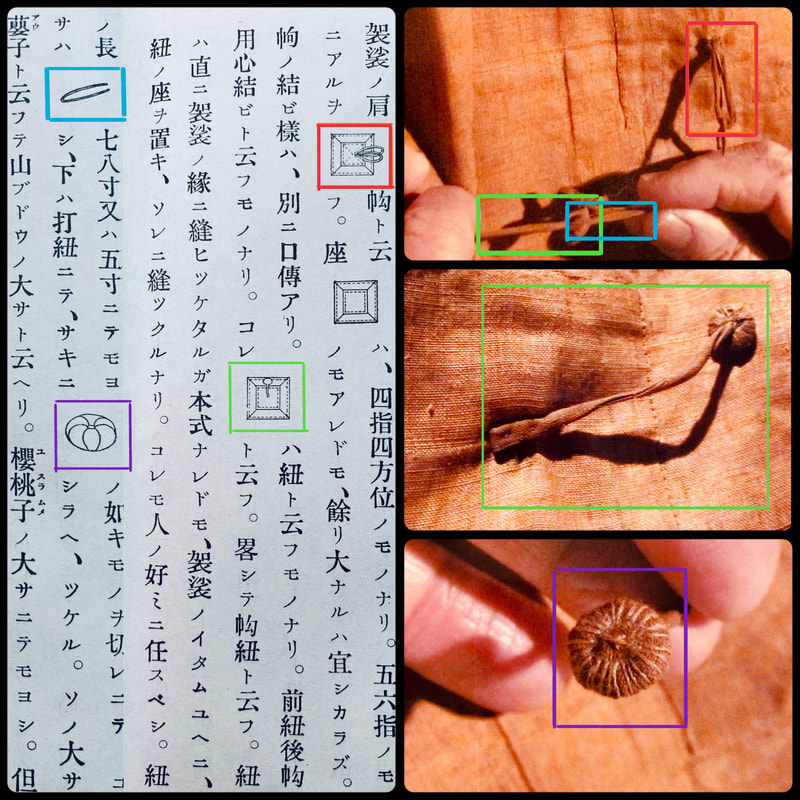

According to the vinaya, the cord is referred to as a kōchū or genchū, but it’s easier to use the more common term himo (紐). 4 In the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, it is written: "The kesa goes over the shoulder, and the kō [himo forming a double loop] fastens with the chū [a small knot at the end of the other himo] in front of the chest. There are three types of chū: ikushi, or ōikushi (薁子 or 蘡薁子, “wild grape seed”), kishi (梨子 or 葵子, “hollyhock seed”), and rishi or tōrishi (梨子 or 棠梨子, “birchleaf pear”). On the kesa, add a thin layer of cloth and cut a hole in it; this is where the kō is attached." That is, the cord is tied in a double loop with a knot called the chū (紐) or “same-mind center tie” (同心結, dōshinketsu). Usually, the knot forming the two loops is placed above the daiza, but to make it stronger, it’s acceptable to place the knot beneath/inside the daiza instead. As shown in the figure at right, three different shapes of chū are fashioned out of either cloth or cord and pushed through the two loops, or kō (鈎). Kō and chū are not intended to be decorative, so there’s no need to use expensive materials or make them fancy. The new translation (Mulasarvastivada Vinaya) says “front cord, rear hook,” while the old translation reads, “front hook, back cord.” In fact, where the new translation would call for a kō, modern nyohō-e fasten with cords, bypassing the chū altogether; that is, both front and back are cords. That differs from the vinaya, but considering how we live and work with the robes, two himo are more convenient. It’s not clear when the practice of using two cords came into being. Jiun Sonja’s Hōbukukasangi reflects the hook system of the vinaya, but his robes, which have been preserved, employ the same two-himo system we use today. |

Cord placement

Proper positioning of the robe is important, so the placement of the cord merits mention.

Placement of the cords on either the front or back of the kesa is an important question, but it isn’t made clear in the vinaya. We attach the rear cord (that is, the cord on the shoulder side) on the outer side of the kesa, and the front cord (the one on the chest) on the inner side.

Horizontal placement

The vinaya states, “Fold the robe in three parts, and secure the kō and chū at the folds,” so the proper placement of the cords is determined by dividing the kesa into thirds.

Jiun Sonja, simply because he altered the placement of his cords in accordance with the vinaya, had his name expunged from Yachūji’s rosters. This placement of the cords according to the horizontal measurement of the robe is completely different from that of commercially made kesa.

Vertical placement

There are three approaches:

Typically, we use the second approach.

In the vinaya, we find such recommendations as “Conform to the size of the body,” “It might be far or near,” and so on. Clearly, there was no problem in adjusting the cords up or down to fit the circumstances.

Daiza

In Kikiden, we read, “The square patch is five fingers’ width and secured on all sides.” This is a reference to the daiza, which secures and fortifies the cord, protecting the kesa from harm.

The daiza is a square; the standard measurement across is 8 centimeters (about 4 fingers). For strong fabric, one layer of cloth is enough, but it’s acceptable to use two layers or more.

Kakuchō

On the four corners of the kesa, we find small squares called kakuchō (角帖). Known also as shōchōshi, shikaku, shikakuchō, jōro (助牢), and so on, they are attached to fortify the corners of the robe.

The size of the kakuchō isn’t fixed, but typically it’s the same width as the border. There is one method of attaching the kakuchō on top of the border and another method of inserting it underneath; we do the former.

In sewing a kesa, please carefully consider the details of the standard measurements.

Proper positioning of the robe is important, so the placement of the cord merits mention.

Placement of the cords on either the front or back of the kesa is an important question, but it isn’t made clear in the vinaya. We attach the rear cord (that is, the cord on the shoulder side) on the outer side of the kesa, and the front cord (the one on the chest) on the inner side.

Horizontal placement

The vinaya states, “Fold the robe in three parts, and secure the kō and chū at the folds,” so the proper placement of the cords is determined by dividing the kesa into thirds.

Jiun Sonja, simply because he altered the placement of his cords in accordance with the vinaya, had his name expunged from Yachūji’s rosters. This placement of the cords according to the horizontal measurement of the robe is completely different from that of commercially made kesa.

Vertical placement

There are three approaches:

- Rear cord 4 fingers’ width from the top border; front cord at the border’s edge

- Rear cord 8 fingers’ width from the top border; front cord 4 fingers’ width

- Both rear and front cords 4-5 fingers’ width from the top border

Typically, we use the second approach.

In the vinaya, we find such recommendations as “Conform to the size of the body,” “It might be far or near,” and so on. Clearly, there was no problem in adjusting the cords up or down to fit the circumstances.

Daiza

In Kikiden, we read, “The square patch is five fingers’ width and secured on all sides.” This is a reference to the daiza, which secures and fortifies the cord, protecting the kesa from harm.

The daiza is a square; the standard measurement across is 8 centimeters (about 4 fingers). For strong fabric, one layer of cloth is enough, but it’s acceptable to use two layers or more.

Kakuchō

On the four corners of the kesa, we find small squares called kakuchō (角帖). Known also as shōchōshi, shikaku, shikakuchō, jōro (助牢), and so on, they are attached to fortify the corners of the robe.

The size of the kakuchō isn’t fixed, but typically it’s the same width as the border. There is one method of attaching the kakuchō on top of the border and another method of inserting it underneath; we do the former.

In sewing a kesa, please carefully consider the details of the standard measurements.

1 In traditional Japanese measurements, four fingers above the ankle would be two sun; in metric, seven or eight centimeters.

2 (六物図述義) Commentary on the Guide to Six Possessions of Buddhist Monks written by Jōdōshinshū (True Pure Land School) priest Enkai (円解, 1767–1840). The Guide to Six Possessions of Buddhist Monks was written by Yuanzhao (Ganshō 元照, 1048–1116) who was in the lineage of the Chinese vinaya Master Daoxuan. “The Guide to Six possessions of Buddhist Monks inspired Japanese commentaries during the medieval period that kept kesa studies alive and provided a basis on which Tokugawa reforms could grow” (Diane Riggs, 2010).

3 (寸) Japanese measurement approximately equivalent to one inch. Ten bu (分) equal one sun; ten sun equal one shaku (尺).

4 The character 紐can be read as himo on its own or as chū in compounds such as鉤紐 (kōchū) and 鉉紐 (genchū).

2 (六物図述義) Commentary on the Guide to Six Possessions of Buddhist Monks written by Jōdōshinshū (True Pure Land School) priest Enkai (円解, 1767–1840). The Guide to Six Possessions of Buddhist Monks was written by Yuanzhao (Ganshō 元照, 1048–1116) who was in the lineage of the Chinese vinaya Master Daoxuan. “The Guide to Six possessions of Buddhist Monks inspired Japanese commentaries during the medieval period that kept kesa studies alive and provided a basis on which Tokugawa reforms could grow” (Diane Riggs, 2010).

3 (寸) Japanese measurement approximately equivalent to one inch. Ten bu (分) equal one sun; ten sun equal one shaku (尺).

4 The character 紐can be read as himo on its own or as chū in compounds such as鉤紐 (kōchū) and 鉉紐 (genchū).